Sand mining in the Mekong : Guest post by Dr Christopher Hackney

As a child, I remember spending ages on the beach building sand castles, trying to keep the sand off my sandwiches and finding half the beach the next day on my bedroom floor. To many, these are the images that get conjured up when you start talking about sand. It wasn’t until I started my post-doc research on sediment transport in the Mekong River, Cambodia, that I began to appreciate a completely different side to the humble grain of silica. Connecting through Dubai on our flights out to South East Asia, the vast amounts of sand being used expand the city and grow the skyline were hard to ignore. This was countered by the sheer size of the desert that backs on to the Emirate – surely there was enough sand right on their doorstep to support their growth plans? Unfortunately not, as it turns out desert sand is too smooth to be used in cement and construction.

Landing in Cambodia it was clear that sand was in high demand. All around Phnom Penh the river was strewn with suction dredger platforms and dredging vessels pumping up sand from the river bed. However, the true impact was only visible after we had undertaken our sonar surveys of the river bed. Hundreds of pock-marks meters in diameter and up to six meters deep were visible all across the bed highlighting just how much sand was being removed. On the water’s surface, the pumps kept pumping and the sand kept flowing, while below the water the river bed was being stripped by the second - physical impacts of the extraction industry hidden in plain sight by sediment laden water.

Yet this is not an issue confined to the Mekong. The need for better regional and international awareness and governance around sand mining is becoming ever more abundantly clear. In a recent comment in Nature (“Time is Running Out for Sand”) Mette Bendixen, Jim Best, Lars Iversen and I develop a series of seven key steps that we believe are necessary and time-critical in order to address the key sustainability issues around global sand extraction from river systems. Firstly we need to identify sustainable sources of sand that map onto other sustainability schemes such as the UN sustainable forest management plan. We also need to look at replacing sand in as many industries as is possible. For example, recent research has highlighted that up to 820 million tonnes of sand a year could be saved by using recycled plastic can in concrete as a replacement for sand (Thornycroft et al., 2018). On top of this, reusing demolition waste as rubble and alternative aggregates will help in the overall aim of reducing our need for sand. This can also be helped by finding alternative construction materials or developing more ‘sand efficient’ building designs. At the international level, there is a pressing need for efficient governance structures which can develop and impose good-practice guidelines for sand extraction.

All of these above steps are underpinned by two key factors that are required to ensure the longevity and effectiveness of any attempt to manage global sand extraction. At the grass-roots level we need better education and awareness of the global sand crisis, the environmental impacts of the extraction process and issues regarding social equity, inclusivity and gender. This is something that can be addressed, and must be met, by a range of people including scientists, the media, governments and the extraction industries. However, fundamentally we are in desperate need of a better global monitoring network to identify the locations and rates of extraction industries. On top of this, and more broadly, we need to have a better understanding of the amount of sand that is available for extraction worldwide. Without this basic information, there is no way that we can achieve sustainable sand extraction.

We all have a responsibility to make these issues public knowledge and to ensure that the joys of playing in the sand can be enjoyed by generations to come.

References:

Bendixen, M., Best., J.L., Hackney, C.R., and Iversen, L.L. (2019) Time is running out for sand, Nature, 571, 29-31, doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-02042-4.

Thorneycroft, J., Orr., J., Savoikar, P., and Ball., R.J. (2018) Performance of structural concrete with recycled plastic waste as a partial replacement for sand, Construction and Building Materials, 161, 63 – 39. Doi: 10.1016/J.CONBUILDMAT.2017.11.127

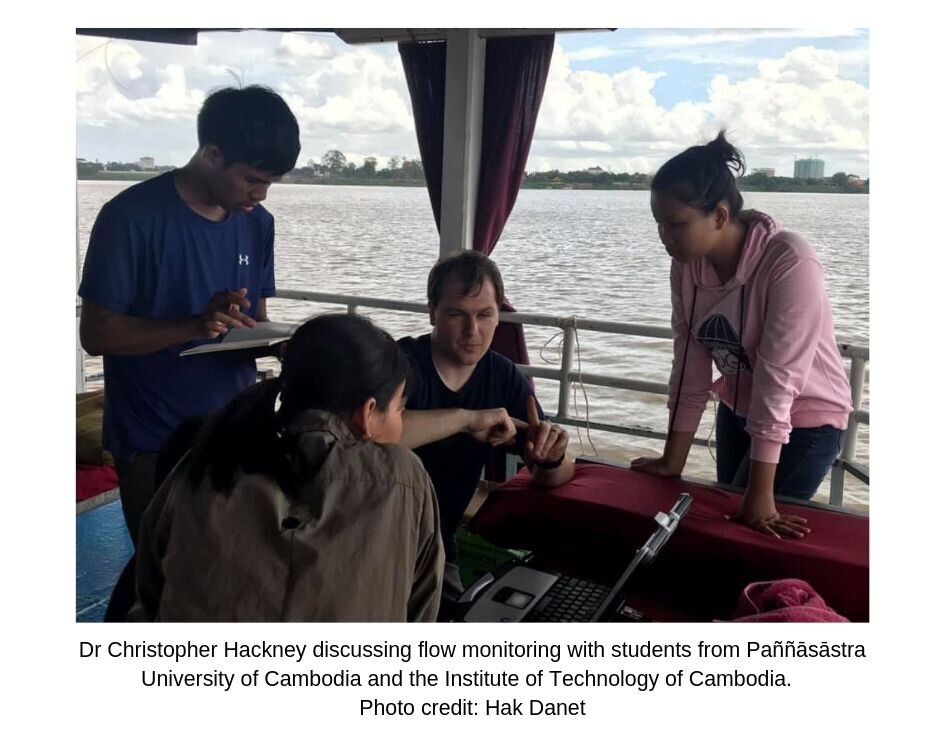

About the Author:

Christopher Hackney is a post-doctoral research associate in earth surface processes and sedimentology at the University of Hull. His research focuses on the processes and mechanisms of sediment transport, erosion and the subsequent morphodynamics of large river and deltaic systems. From 2013 to 2015, Christopher was the post-doctoral researcher on a NERC-funded project investigating sediment transport, erosion and deposition in the one of the World's largest rivers, the Mekong. He obtained his PhD from the University of Southampton in 2013 for a project focused on the numerical modelling of incised coastal gullies and the impact of their evolution on climate change and sea-level rise.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author/s and they do not necessarily reflect the views of SandStories